The Genius of Digital Detox

The Genius of Digital Detox

The movement and the person, by Bill Softky

If we’re lucky, the name Fidget Wigglesworth will go down in history as the father of the Digital Detox movement and the savior of humanity.

I’m not kidding. Digital dependencies and diseases are a mental-health epidemic (more on that below), and Fidget found a cure: summer camp. The ideas is simple: treat grownups like kids again, and they’ll feel like kids. It works because he really thought through the camp experience, and delivered. The resulting adult summer camp run these last few years by his Digital Detox movement, “Camp Grounded,” has been optimized in a dozen crucial ways to meet the sensory-social needs of adults frustrated by the insults of technology. In other words, it’s fun.

Fidget died last January of a horrible brain cancer, leaving behind a tight family and group of friends, still together since bonding as kids at Jewish stay-over camp decades ago. Last weekend was the first session Camp Grounded has run without him. Many people had known Fidget and shared their memories over the weekend, often crying.

“Fidget” was his camp nickname, not his real name. Using nicknames in place of real ones is one reason people at camp connect so well: no one knows if anyone is famous or important, so everyone gets treated like an ordinary person, not a networking conquest. That’s one of many genius ways in which the camp encourages live human connection (other tricks: no talking about work, nor about time, nor about categorizing people in any way). Using little rules like that, Fidget had flipped social conventions on their head, inventing new ones to increase spontaneity and authenticity. And of course the hallmark rule, not devices of any kind. You have to check them at the gate, and get them back when you leave. No exceptions.

This year’s first session of Camp Grounded, spanning last weekend in the Mendocino Redwoods, was wonderful. A few hundred people played in every way possible: at Frisbee, at rock-paper-scissors, at yoga, on guitars. Live music everywhere, all weekend, hikes, crafts galore, dances, skits, and a talent show which lasted all night. Some people could sing or dance amazingly; some just wanted to face their fears of public speaking. All were cheered equally.

Even me. I got up to try a “Mr. Science” shtick, giving quick and simple answers to off-the-cuff questions like “How do magnets work?” or “Why do we find minor key music sad?” People liked my answers, and cheered me as well. The stage experience felt like a bubble-bath of social approval. Even the next day I got high-fives.

Science is why I was there in the first place. Last year my wife/collaborator and I were invited to Camp Grounded to teach an especially deep form of meditation, designed from first principles of neuromechanics. We loved the camp so much we’ve come twice more since. This year we came with amazing news for us personally, and for Digial Detox as a whole: the research paper we wrote describing digital dependencies had finally passed peer review at a prestigious journal, and will appear this summer. This event suddenly makes our theory of problems like “screen addiction” the most complete scientific answer yet. (But we couldn’t talk about it there, since it was “work.” So we had fun instead.)

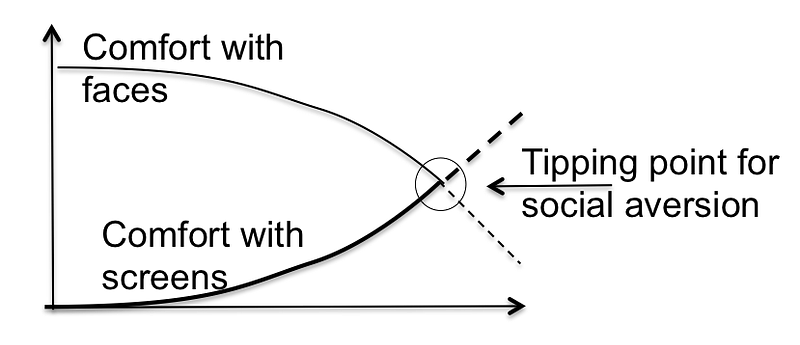

In that sense she and I understand the theory of digital diseases better than anyone. We don’t just have the numbers on the epidemic, we have the equations. But Camp Grounded has the cure. They already heal digital damage better than anyone. In our view, problems with devices of all kinds come down to sensory deprivation: our nervous systems need complex, real-time, full-spectrum sensory input, and starve on mere trickles of pixels. Especially when connecting with people. In that view, the best cure for the lonliness, depression, and anxiety caused by online life is to be face-to-face with fellow people in a natural, un-incentivized environment.

Guess what? That’s exactly what Camp Grounded does. They figured out the cure without having the equations, and it works. This can’t come at a better time, because humanity really is at risk. By “humanity” I mean not just human lives, but human empathy. Empathy needs physical proximity, and is crushed by digital interaction.

The weekend’s closing ceremony invoked Fidget’s name a lot. We were on a sunlit lawn among the most beautiful tall trees on the planet, their leaf-tips spring green and the treetops waving gently in the wind. Over four days we had each made so many new friends and done so many weird, unexpected things that we forgot the outside world. Being human among other humans was just plain fun again, so we each got a crucial reminder of what life can be like. They invited me to explain the science in layman’s terms. I started with gratidude, for the beautiful environment and weather, and for Fidget’s inspiration and everyone’s hard work. I talked about the grandeur of the trees and the subtlety and awesome bandwidth of our sensory systems in real life, contrasting the continuous 3-D richness of the grove with the puny intermittency of digital signals.

But the real story isn’t the scientific explanantion, it’s the live experience. Fidget, his family, and his friends have created a temporary tech-free oasis in the wilds of Northern California, three hundred people on a giant lawn in a forest, looking each other in the eye and knowing this is how life ought to be. Camp Grounded made it work. So whatever happens to them without Fidget, they’ve already done the most important part: found a way to bring us back to sanity, and shown it’s actually possible. Now it’s our turn.