The Ratchet of Truth

The Ratchet of Truth

A utopian short story by William Softky and Criscillia Benford, narrativizing a software proposal written as an entry to a contest combatting “Fake News.”

“I was going to tell you that Mark Twain said: ‘A lie can get around the world before the truth can get its boots on,’” Ed told the men seated around a jewel-toned table in a sumptuous conference room that reminded him of Venice. He stood at the front of the room, between the table and a whitewall.

“I was going to say that,” Ed said, smiling. “But I found out this morning that Twain never said it, while dozens of other people said something very close.” Ed placed both hands on the old-fashioned table and leaned forward.

“Lies are fast and truth is slow. Version 1.0 of that idea came from Jonathan Swift in 1710:

Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it

“A dozen re-quotes later, in 1820, a newspaper in Maine printed something that would be attributed to Thomas Jefferson twenty years later, and then to Mark Twain ninety years after that:

…for falsehood will fly from Maine to Georgia, while truth is pulling her boots on

“So weirdly, a famous and funny quote about the speed and reach of lies is wrapped up in a lie. Or maybe not so weirdly. Claims about the transmission speeds of lies are quantifiable. So that quote and its many variations are attractive expressions of a mathematical truth about information flow.”

Ed paused to observe how this last sentence had landed. Nobody was looking at a phone. Each man sat facing him, more or less. Some were sitting upright. Good. Ed continued:

“The speed with which a lie travels is easy to calculate. In the 1700’s, the fastest lies moved by horse. In the 1800’s by railways, and then by telegraphs, which placed limits on their form. Now, with the internet, lies can take virtually any form and cross the world at light-speed. The climate for Truth was already shaky three hundred years ago, in Swift’s day, but today lies can reach a million times more people a million times faster. Now wordwide, truth is drowing in lies, connection is drowning in gossip, and real live teenagers are killing themselves. Messages are easier to copy than ever. Lies are fast. The truth is slow. These three truths add up to one huge problem.” Ed paused for effect. “Fortunately . . .” Ed paused again. “There is an answer.”

A hush. Followed by coughing and the sounds of men shifting their weight. This was going well, Ed thought.

Ed’s answer to the “Twain problem” — the only answer, really, as far as Ed was concerned — was called The Ratchet of Truth. Ed believed that the men who sat beside him would be essential to any plan to preserve Truth in the commercial world. If these titans of the authenticity industry deployed The Ratchet in their companies, the equations would change. Yet Ed knew they wouldn’t bite unless he could persuade them that now was the time to change the world for a second time.

The Ratchet was first conceived during the Entropy Crisis, when the scope of the Digital Dependency epidemic became clear. As with all plagues, mothers were the first to know, and in this case every mother in the world feared the twinned scourges of “screen addiction” and “fake news.” Every mother knew at least one once-vibrant child who grew into a hunched and angry adult self-sentenced to solitary confinement, sensory deprivation, and paranoia.

In retrospect, the two core problems should have been obvious. First: what happens when most jobs and most algorithms require manipulating or evading the attention-management systems of fellow humans, especially children? Lots of people get manipulated. Lot of children get manipulated. They notice. Second: what happens when you take the planet’s most sophisticated multisensory 3-D signal processing platform, the human brain, and subject it to serial hours of oculocentric, fractured input from a tiny 2D piece of glass? That brain starts to prefer screen input, once signals from the “real world” overwhelm it. In retrospect, we should have asked a simpler question: what happens when a global culture develops the practice of eating human brains?

After things got really bad, they got better. Ed had played a role. But if there is a hero in this story, it isn’t Ed. It isn’t even The Lions (a group of CERN physicists, musicologists, philosophers, art historians, linguists, historiographers, and narratologists) who first recognized and tackled the twin scourges that had been unleashed by the attention industry.

If there is a hero in this story, it is not a person but an organization, in this case CERN (Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire). CERN allowed the Lions to work together in physical space. There they shared ideas about timing, memory, cognition, selfhood, representation, quantification, Truth and more. They shared books and computer code, conversation and beer. They figured out how to listen to each other speak their “native” professional language. Their collegiality was legendary, and their decades-long collaboration was necessary to cement the trust which made working on the impossible possible, and made crazy answers not only palatable, but sometimes delicious. The Lions themselves were only human — that was their main point, after all — and could have been anyone from any country.

Together, and only together, The Lions turned the Media echo-chamber into a Fabry-Perot laser cavity, and human bodies into fractal harps. Business fads and orgasms alike surfaced as eigenfunctions with resonance modes.

The attention industry attacked with all its might. The Lions fought back from their fort at CERN. But with equations as their only weapons, and no revenue stream, The Lions knew that only an extraordinary strategy could protect their scientific findings from obliteration by the attention industry. This David/Goliath conflict, little science against Big Commerce, played out in a media field of battle literally owned and maintained by Goliath, making the old global warming attacks look like tiffs. Some recorded versions of the equations said victory in these circumstances was impossible. That is, victory for living humans, distinct from spreadsheets processing production metrics.

How could mathematical truths about human needs be protected from infection by institutions, some of which benefit from their ignorance? How can humans survive in an environment where ignoring human needs leads to profit?

The Lions took this as an intellectual challenge, in fact the greatest intellectual challenge that would ever be posed. At the point when CERN took them in The Lions had only re-posed the unsolvable problem of the survival of humanity as an unsolvable mathematical problem in physics and information-theory. But reposing the question in mathematical terms was a great leap forward, because unsolvable physics problems are red meat to the likes of the particle physicists who had joined the Lions.

Inspired by the physicists among them, the Lions articulated the central dilemma like this: anti-profitable messages propagate through a profit-driven economy like balls roll uphill. They don’t. The comparison inspired The Ratchet, but the Lions couldn’t build it because of a second development.

The Lions realized that society’s progressive loss of faith in digital representations, epitomized by the Fake News Floods of 2027, was in fact a harabinger for the popping of a larger “representational bubble.” Their model took after financial bubbles: when faith in any system begins to collapse, network effects ensure it collapses very fast, like a bank run. And when the digital-representation bubble finally popped, one evidentiary stack undergirding public-health after another toppled like a house of cards, just as predicted. Soon after, anything digital, anything re-writable, became suspect.

The Lions had also predicted digital distrust would accelerate toward a Singularity of Trust, and in fact it did. Because of their warnings, the worst of The Singularity was avoided, equations were deployed to mitigate its effects, and vibratory social capital was rebuilt worldwide through the now-ubiquitous resonance gatherings in community parks. Just like a million years ago, vibratory human connection saved the day. Chains and webs of resonant humans connected the mass of living humanity with those few scientists, the Oracles of the Ratchet, trained to safeguard Truth.

As trust in warm human bodies rose, and trust in institutions dropped, the Anti-Branding Revolution spread. An especially close group of powerful friends who called themselves “The Foundation of Philanthropists” kept the Revolution non-violent. Foundation members personally established the authenticity industry, whose “services” have prevented literal informational chaos since then. At first the industry relied on Oracles (and their still-secret Ratchet) as a black box ensuring the truth of social compacts regarding water and disease, and relied on Foundation members who waged their own lives on that truth by drinking that water, members who themselves had never seen The Ratchet. This was how Authenticity, a concept quantified by The Lions and implemented by The Foundation and the authenticity industry, ended up saving the world.

But not permanently.

Now, years later, these authenticity leaders wanted to learn more about The Ratchet of Truth, Ed’s specialty. Possibly even to buy it, or rather buy into it. Everyone knew their services, levees of a sort, would not be able to hold back the flood waters forever. Once, again, lies proliferated.

When the four CEO’s had introduced themselves, Ed labeled them as characters from Shakepeare’s Julius Caesar, Ed’s favorite crystallization of the working of the character-types of power: first Brutus (older and professorial), then Julius (middle-aged and visibly powerful), and Mark Antony (young, stylish, ripped). No treacherous Cassius in this crowd. The lone man at the end used his name but not his title. Maybe he was in the press. Ed named him Pressman. The others clearly knew him.

Ed was proud of himself for convening these men, the titans of authnticity. But he felt strange as he stood before them. He was an economic nobody. He was out of his depth. He could explain why he was there. He wanted them to deploy The Ratchet simultaneously, ratcheting the Ratchet itself irreversibly, past its global statistical tipping point, to crystallize human knowledge. But he wasn’t a salesman. His only skill in business had been as an explainer and simplifier. His “great ideas” mattered — they had helped build The Ratchet — but they weren’t profitable. Yet.

“Before you tell us about the latest Ratchet software,” observed Brutus, the soothing tones of his aristocratic British voice filling the room, “please let me say first and foremost how personally glad I am to be among friends I have seen separately but only at this moment all together.” The old man looked at each fellow CEO directly, in succession. “We didn’t just do good work, we had fun doing it in 3-space.” He paused, a faint catch in his voice. He let the silence hang almost a full second longer than one usually would. “That’s what authenticity is really about. Thanks.” He nodded, and then paused before continuing.

“Also, I’d like to say how honored I personally am to hear about this software from Ed. I’ve known about his work for decades.”

Ed was surprised, but smiled gamely. He had figured people like Brutus — no matter how old — forgot about everything ancient, or at least ancient in internet-years.

Long ago, Ed had written (as a minor co-author) one of many early scientific articles with The Lions, who were later honored by The New York Times as “the greatest group of geniuses since the Manhattan Project.” Ed’s involvement had been random luck, pure entropy. But the paper itself predicted the Singularity, tamed the Anti-Branding Revolution, and launched the Ratchet. He was now the only of its authors left alive.

“I appreciate the shout-out,” Ed said. “But since I’m here to talk about the whole Ratchet, not just the one gear I tinkered with, I suppose I should start by clarifying a common misconception: the Ratchet isn’t software.”

Brutus startled as if stung.

Julius, wearing a smiling “executive face,” half-joked, “If it’s not software, can I skip the licensing fees?”

“Sorry, not quite, it still has upkeep,” Ed smiled back. “The Ratchet works very much like software. Think how a spreadsheet calculates numbers. The Ratchet does the same thing, calculating what is true. Think how a graph shows why a model fits the data. The Ratchet shows why truth is true.”

Julius nodded, but still looked dubious.

“Let me try again,” said Ed. “The Ratchet is actually a specific mathematical framework for information processing, which contains a well-known user interface that has become colloquially known as The Ratchet.”

Ed paused, observing that Julius’s face had relaxed, slightly.

“What makes the Ratchet unique, and uniquely effective, is the all or nothing deal,” Ed continued, “its collective spiritual aspect.” He regretted those words as soon as he said them. A hush fell, once again, but this hush was full of skepticism.

Ed did repair immediately. He smiled as if he had been joking, and observed casually, “The term ‘the Ratchet’ has tons of different meanings, just like ‘the internet.’ Just like ‘collective’ and ‘spiritual.’ I can imagine that some of these words alone might raise red flags for you, even more when you put them together. ‘Collective.’ ‘Spiritual.’ About as far from rational capitalism as can be. What do you think?” Ed knew the titans each adhered to The Lions’s well-established theory of Optimum Negotiation. He knew they would understand his question as a reminder that in this moment they had decision-making autonomy, and could co-direct the discussion.

All nods. So far, so good.

Ed went on, “The Ratchet was invented to combat a growing problem at the intersection of mass media and social media. Like viruses, messages have a spreading rate increased by profit and attractiveness, and decreased by slower, costly, unreliable validatation. Like a synthetic virus, the right kind of lie can spread faster across time and space than any other human pathogen.”

Mark Antony, leaning over the table more like a sprinter than an executive, raised his hand as if in class. “So that’s the mathematical truth your Mark Twain quote talked about?”

“Exactly!” Ed gushed. He had hoped for someone anticipating a key point to reinforce his credibility. “Lies are fast and Truth is slow. How can Truth outpace lies when the very message-propagating properties of the medium itself give tail-winds to lies? What if truth, even after discovery, always faces head-winds from the message-passing infrastructure?”

Brutus leaned back professorially: “Fine. Where does that leave us? How can we trust anything at all?”

Julius nodded instinctively, while Mark Antony smiled as if he knew the answer. Pressman said nothing.

“Again, exactly! You’ve nailed it,” said Ed. Oops. That sounded condescending. Ed adjusted his tone. “The Lions regarded the problem you’re highlighting as the greatest intellectual problem in history: how to re-deduce scientific and historical truth from scratch?”

Mark Antony interjected, “Reminds me of Wanamaker’s dilemma. He said, ‘I know a third of my ad budget is wasted, but I don’t know which third.’”

Soft chuckles. For a brief moment everyone at the deliciously smooth table was touching it with their fingertips, and looking at their hands. Some had forgotten that the famed adage about ads masked a much deeper truth about the untrustworthiness of data which is shot through with unidentifiable falsehoods.

Brutus countered, “Sure. But Wanamaker never solved his problem, nor has any ad executive since, nor anyone else. If your database and your recording apparatus are corrupted at the same time, there’s no going back. You have no idea what is true and what isn’t.”

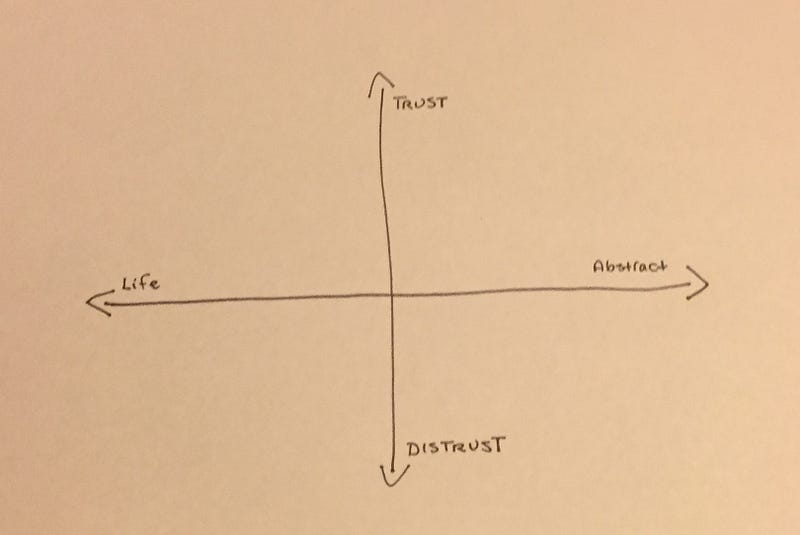

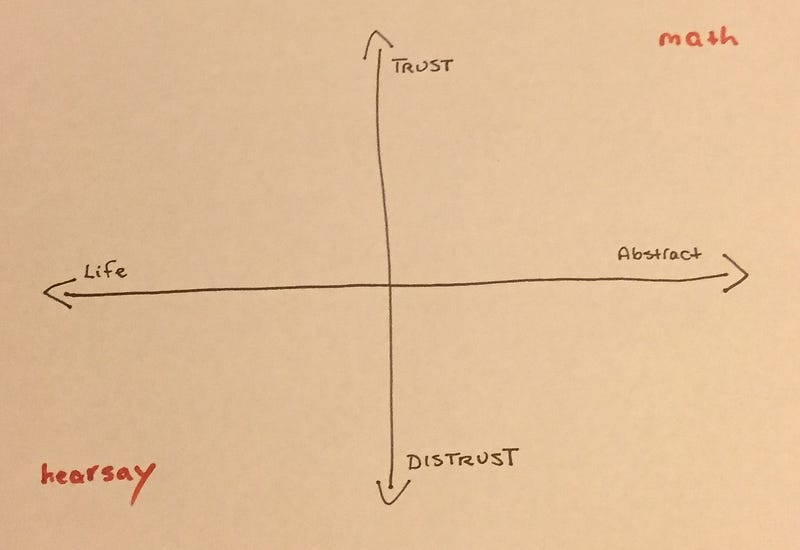

Ed saw where this was going, and changed course. “OK, everyone tell me two to four things you trust. Trust a little, trust a lot, doesn’t matter, we want diverse examples. I’ll start: I trust hearsay, and mathematics.” He turned around and walked to the whitewall. At middle-height across the entire board he wrote the organizing axis, like this:

After that, in colored pen, he wrote “hearsay” on the lower left, and “math” on the upper right.

The men leaned in, and spoke without waiting or raising their hands. “Science.” Ed wrote “science” near the upper right. “My own records.” Middle left. “My senses” Upper left. “Guts” Upper left. “Scientific literature.” Way upper right. “Memories” “Peer-reviewed scientific literature.” “The law of gravity.” “Information protocols” “E= M C²” “Newspapers.” “My friends” On and on, each word finding its place on the giant map.

After a minute, the wall was covered with words. Ed had written each in a different specific location on the wall, using both horizontal and vertical space, sometimes even swapping out colors to make spontaneous conceptual art. Ed pointed to the very top, the very summit of Mount Everest.

“So we start here, as high as we can get,” Ed said. “The most trustworthy information sources of all.”

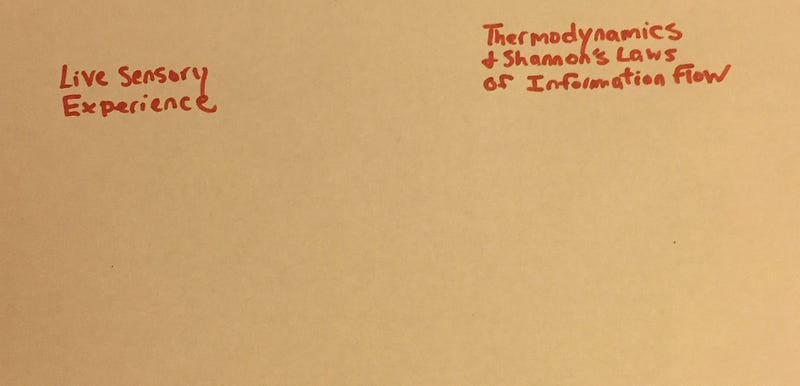

The very top of the board looked like this:

Ed waited while the group pondered his implicit point: in a land of continuous variation of trust, only a precious few information sources are truly unimpeachable.

“Sensory experience is the most trustworthy thing a human can feel. Thermodynamics is the most trustworthy principle a scientist can invoke,” Ed said. “Which do you pick?”

Julius spoke first: “Thermodynamics. It stays still. Scratching my ass is a live sensory experience, a wonderful one but not very durable.”

Brutus guffawed, sanctioning more laughter from the others.

Laughter suited Ed perfectly. He asked, “Has anyone read Isaac Asivmov’s short story ‘The Last Question’”? Heads nodded, even Pressman’s.

Mark Antony brightened again. “I loved loved loved that book as a kid,” he said. “I would never have understood entropy without it.” Now the room was looking at him, so he continued, his salesman’s swagger easing into the story. “I was a kid, and everyone said this story was amazing. It was. In a few pages it spanned all of future history, from now to space travellers to star travellers to time travellers and somesuch posing the same issue each time. Every generation asked their best computer the same thing: Can the thermodynamic arrow of time called ‘entropy increase’ ever be stopped and reversed? That’s like asking about God. And every time the computer said it didn’t have enough data. Until the end, when it did.”

Brutus mused, “That sounds like a Hollywood end-the-world movie.”

“Even better!” Mark Antony crowed. “This was about the end of the whole fucking universe, written indelibly in the script of God, thermodynamics. Could a teenage boy hope for a more badass vision of the future?”

Silence. The others did not seem to share Mark Antony’s enthusiasm for the story’s plot.

Ed appreciated the pause for a moment, and then continued speaking as if Mark Antony’s comment had been part of his own lecture. “That little story trained a whole generation of future scientists. Its impact was huge. A whole generation learned everything is dying of diffusion, slowly spreading thin and wearing down.” He let the somber note linger.

“But that’s wrong.” Ed announced suddenly and dramatically.

“What?!?” Brutus asked, his face a mask. “You’re denying the Second Law of Thermodynamics?”

“Oh no, I would never piss on the Second Law. But the Second law only applies to closed systems, like the entire Universe all at once.”

Mark Antony asked smugly, “But aren’t we part of the Universe?”

“Yes, but that’s the problem. Earth receives heat at high temperature from the Sun, and sends colder radiation into space, so we’re not a closed system.”

The smugness had left Mark Antony.

“So entropy increase isn’t the problem on Earth. In fact, it’s the opposite of the problem. All around us entropy is decreasing, because material culture and life itself involve copying things, whether DNA or memory registers. Copying by definition reduces the range of available patterns, and thus reduces entropy. Copy DNA, reduce entropy. Have offspring, reduce entropy. Fill your disk, reduce entropy. Conquer a market, reduce entropy.”

Ed’s passion (and voice) began rising. He pushed down on the heavy table for emphasis. “Succeed as a species, a kin-group, a culture, every algorithmic accounting of the selective survival of any pattern shows diversity and entropy go down, not up!” In his enthusiasm, Ed had almost lost it, but this speech at least caught everyone’s attention again. “And entropy-reduction doesn’t slow down gracefully, it speeds up, accelerating toward a singularity.”

Brutus summarized; his accent and demeanor made it difficult for Ed to know if he was mocking Ed’s point or just repeating it in his own words. “So our little bubble here on earth has been exempted from the physical inevitability of Asimov’s heat-death. So we can be happy we’re not dying of diffusion. But not too happy because we’re still dying of the very opposite, of standardization and scaling and sameness? Everything becoming copies of everything else. Diversity, variability evaporating?”

Brutus waved his hands as he talked, scowling at some terms and animating the images so well that everyone nodded with comprehension. Ed didn’t have to say anything.

Julius put a finger on his lip as he faced Mark Antony. “Wasn’t ‘The Last Question’ the story that first warned about the Trust Singularity?” he asked the younger man.

“No, that was a different story, ‘The First Last Question,’ written later by someone else,” Mark Antony replied. “That later story invoked Asimov, because it was about this same entropy-reduction thing. As I remember it, the title means there are several ‘last questions’ humanity has to deal with, and entropy-reduction is the first of them. In ‘The First Last Question’ they ask the computers the opposite of Asimov’s question: Can entropy-reduction be decelerated?”

Brutus gazed as if seeing long-lost faces through a window. “I remember that story. That was what got The Lions started. That story inspired them to warn us about the Entropy Crisis. Like Einstein’s letter to Roosevelt about the atomic bomb, initiating the Manhattan project. That short story triggered everything: the cathedral volunteers, the 3-D societies, the whole Manhattan-moonshot mindset, but now all volunteers. Their slogan was, Keep truth alive!” His smile was broad and subtle, buoyed by the proud recollection of an old man. “….and the genius was that all those geniuses actually cooperated, in fact so well they finished years ahead of schedule. I was there.”

Ed cut to the chase. “I’m glad we’re finally back to The Ratchet and fake news. Let’s remind ourselves of the problem at the time. There were tons of parasitic informational organizations. For-profit universities. Media empires. Entertainment conglomerates. Commercial persuasive technology labs. Political biometrics firms. And among them reverberated countless parasitic message structures: Bubbles, Bayesian traps, confidence schemes, siloing platforms, marketing categories, profitable falsehoods, infomercials and advertorials. Bad information was drowning everyone, and society needed a way to hold on tight to some kind of truth before we all went crazy.”

Julius interrupted: “So to keep truth from slipping backwards, they built a ratchet, which I think is one of those steam-punky mechanical things which lets a gear rotate one way but not another. Like the hill-brake on cars.”

Brutus’ added softly, but with confidence, “Is it like a real ratchet which goes click-click-click, or is it like a one-way valve or diode — something to regulate flow?”

“Yes, and yes.” Ed addressed both points at once. “Yes about flow. Truth in Nature doesn’t show up in chunks, like clicks or stock quotes do. So truth-finding as a process has to be continuous. The flow metaphor is perfect.”

Ed turned toward Julius. “And you’re right about the word ‘ratchet.’ It is a metaphor. The central metaphor for communicating how to hold truth in place, how to keep truth from sliding around. In practice, ‘holding Truth in place’ involves recording and defending a given statement according to truth-value rather than its productive value. Think of our dilemma like a computer signal-processing problem: to reach the goal of recording data associated with truth rather than with resources, you need to create a distributed message-passing incentive structure driven by metrics of truth rather than metrics of resources.”

Mark Antony raised his hand so fast he almost jumped from his seat. His smooth shirt pulled tight across muscular shoulders. “So…so! You just turned the undergraduate question of the ages — What is Truth? — into a physics word-problem! Holy shit! Wow. Congratulations.” He seemed impressed, as if he had just watched Ed kick a game-ending goal.

“Thank you,” Ed said. He had never been praised that way by an alpha-jock before. He loved the feeling. “Yes, when you boil it down it really is a physics problem, having to do with the eigenfunctions and null-spaces of message-propagating media. It’s math all the way down. Or equivalently a math problem about incentive structures and scaling, but you get the same answers either way. The Ratchet as an informational structure is the optimum solution.”

“Who built what?” Julius asked, irritation evident in his voice. “I’m tired of all the abstraction.”

Ed was about to answer, but Brutus began speaking. “I remember it. The information-architecture all came from physicists. Some of them were also forum moderators who pondered nerdy questions, like the equations of motion of optimal messaging protocols. It . . .”

Julius interrupted once again. “I’m gonna pose this in economic terms, since I’m even worse at physics than at ass-scratching.” Ed nodded. Everyone seemed happy for a change of voice. “The nicest thing anyone ever calls me is ‘businessman.’ Usually it’s closer to ‘asshole.’ That’s because in business everything has a budget, and messaging costs money, and training costs money, and storage costs money. So every time someone ignores an email, or reads without responding, or fails to file, or fails to archive, on average those decisions about what we keep and what we chuck add up to money: we keep messages which save us time, avoid liability, help us recover faster after interruptions, whatever. But only by chance do we save the funny stuff and the healthy emails, even though it makes us way happier.” It had seemed Julius was winding up for a big speech, but cut it short. “Is it that simple?”

“Yup,” Mark Antony joined in. “The principle that messages demand money in order to save money shows up everywhere. All these big companies which destroy records of toxic waste and stuff. Of course they destroy records! What do you think information managers are paid to do, anyway? Preserve and protect things which endanger their companies and careers?”

Julius took the floor again. “Enough about the problem. What does the solution look like?”

Brutus interevened. “The best place to look for solutions is before the problem appeared, but ever-fewer people remember to look there. As it turns out, there were already lots of sites and platforms whose very structure percolated the good up and the bad down. Let’s call it up-voting and down-voting. Slashdot started it, Wikipedia scaled it, and Facebook monetized it with ever-improving displays.

Wikipedia did quite well, but even there politically provocative material needed constant defense, and the history system was not optimized for hypothesis-validation, like the Ratchet is. Even Wikipedia had to beg for revenue.”

“So,” Brutus drawled on, “The Ratchet evolved based on that collective model, like cathedrals of old. Every volunteer mason carves an anonymous stone for the common project, according to the common plan. Ironically, the first stabs at The Ratchet weren’t by The Lions who coded up belief-nets using Bayes and Occam. The first Ratchet actually came from rhetoricians and pedagogues, who systematically taught Editors and Edmins to identify the logical structure and logical fallacies of common arguments, the necessary first step in dissecting and dismantling Fake News. So-called “critical thinking” is an old-school intellectual training professors seldom get nowadays.”

Brutus looked around the room as he took a few breaths. “Then, after the workflow and data-visualization jocks prototyped the first display, everything really took off. Gamers, ever the experts at brilliant allocation of weirdly limited resources, invented new dark portals through cyberspace to spread word of cyberspace’s faults, and the faults of those portals were submitted to The Ratchet, and then fixed. Since everyone’s collective goal was intellectual harmony in the first place, cooperation flourished and communications became both more efficient and more pleasant, a positive-feedback loop in both senses of the word. The amazing thing was, they built it up from nothing more than a paradoxical phrase embedded in a science-fiction story. The original short story didn’t even tell them how to build it!”

Although that was exactly the message Ed wanted his audience to accept, he realized this was taking longer than he had planned. “Yes, even those early versions of The Ratchet helped bolt down the evidence-stack for major scientific controversies: The Ozone hole, global climate change, and various cancerous substances and medical effects. Then it moved into more contentious areas, like voter fraud. Hopefully it can take on any subject at all. Time after time, the Ratchet holds the line.”

Julius added a bit sourly, “The more you talk about how good it looks, the more I want to see it with my own eyes.” There was sudden energy. They all clearly wanted to look at something instead of just having to listen. “May I see it?”

“No.”

“No?” Julius’ eyes widened.

So did Mark Antony’s. “Really, no?”

“No. You can’t see it. We’ve found that instinctive reactions are guided by variability in people’s preferences regarding color, font, and latency. Those change all the time as part of front-end evolution. The backend and concept architecture are what matter, so in fact no one can use or even see the actual interface except as part of a certification class.”

“That seems lame,” Julius said in as even a tone as possible. The others matched his skepticism.

“I understand your concern. It happens all the time, because this is the test of faith. If you really believe it’s designed to do its job by people who understand the job and are incentivized the right way, and tested on those metrics, you ought to believe it works even before you see it. We don’t want you to make decisions on superficial features, when you only need the gist.”

Ed semi-bowed with almost Japanese formality. “So, with your permission, I will provide a suitably low-res version whose details can’t be criticized.” He turned away from them, furiously erasing all the words on the whitewall until it was again blank. He raised both hands as if describing the user-interface spread across it. From behind, he looked like a prophet raising his hands to the heavens.

Still holding his hands up, he spoke to them over his shoulder. “At the top, like on this board, you see the original claim, a hypothesis which may or not be fake. Like one of the example bogus claims which started the whole thing.” Across the top he wrote the lines in black,

Anti-Trump protestors in Austin today are not as organic as they seem. Here are the busses they came in.

Ed explained, “Because The Ratchet as a whole is a continuous-valued system for hypothesis evaluation, its user interface puts the primary hypothesis to be tested at the top, and arranges the sub-hypotheses composing it below.” He grabbed three colored pens to scribble three different phrases:

Buses in Austin

Protestors in Austin

Protestors came in buses

Even as he kept the fiction that the whiteboard was a presentation screen, Ed bragged. “Everyone knows particle physicists are the best hypothesis-managers in the world, mostly since their data sucks so much, so they got to design the backend. Each of these hypotheses can be decorated with metadata, like how likely is it in certain scenarios, what are the defaults and distributions, what evidence might render it wrong or moot.” As he spoke he drew multi-colored lines between the boxes, and numbers on the lines, then fattened the lines into free-form rivers of probability, rivers narrowing or widening as they flowed from hypothesis to hypothesis, filling up some, draining others. A multicolored river-map of probability space.

Ed turned his body halfway, so he could gesture at the whitewall and his audience at once. They remained attentive, so Ed soldiered on. “These flow-lines,” he said as he gestured toward the variously-wide rivers of ink connecting hypothesis to hypothesis, “show how the separate probabilities for the separate hypotheses are high, but nonetheless the causal inference about protestors in buses fails, because other hypotheses, like the buses carrying convention-goers, are far more likely.”

Brutus coughed softly.

“For each scenario,” Ed continued, “the backend uses that metadata to calculate relative probabilities, over and over until they settle into mutually-consistent patterns. Maybe there is just one reasonable explanation consistent with itself and with the data, maybe two competing explanations. The front-end will show the unanimity or the conflict through these flow-lines. User can explore — fiddling mostly — until they’re satisfied it makes sense. They can browse the modification history, which has been helpfully organized to highlight biased edits. They can up-vote skillful Editors and Edmins.”

“It’s like the scientific method,” said Mark Antony.

“Yes,” Ed replied. “But this display isn’t just ‘like’ a graphical user interface of the Scientific Method, it actually IS a graphical user interface of the scientific method, hook, line, and sinker. It uses Bayes theorem and Occam’s Razor just like scientists do, and it reproduces results when we give it real data. It’s a legitimate technology for applying the scientific method properly to any assertion at all.”

With the green marker Ed put a green check-mark next to the first two terms, then aggressively circled the final term “Protestors came in buses,” surrounding his red curves with question-marks. “For someone who’s trained, using The Ratchet is like driving a Ferrari through understanding.”

Mark Antony had his usual eager look. “So if you can walk us through the evidentiary trees for those protestors and buses, how about walking us through the decision we’re facing right now? What’s at stake if we buy the Ratchet, big-picture?”

Ed looked relieved. “Perfect question, because I’m basically done. The Ratchet is already in place all over the world, but disjointly: in schools, legal offices, libraries, universities. The final frontier for years has been deploying it in corporations, but your three are the biggest and most important. If you adopt coherent versions and synchronize your root-node hypotheses, a quasi-permanent informational structure isomorphic to Truth will be crystallized for all the world.”

Once again Julius voiced skeptical impatience. “I won’t pay for anything I can’t see, flat-out. Especially if it’s based on woo-woo spirituality, requires special training, and undermines my revenue stream. I bank on rationality.”

“Me too,” said Mark Antony. “And I base my trust on my own sensory experience. I can’t believe it’s true unless I see it’s true, and I need my story and not somebody else’s. That’s how I work, that’s how all humans work.”

Ed smiled. His task was complete. “So we agree!” he said excitedly.

Julius and Mark Antony frowned, looking puzzled.

Ed explained. “Both of those claims are consistent with our hypothesis stack. We believe in rationality over everything as an analytical principle, and we believe in sensory experience as the ultimate human value!” Ed exclaimed.

Julius and Mark Anthony both leaned back in their chairs. Julius spread his arms and legs to take up more space.

“Our principles and values are aligned,” Ed continued. “You’ve basically signed the check! Who cares what colors the callouts are, what font, what platform? As with any web page or any stone, the surface of The Ratchet changes all the time, but underneath stays the same. It runs the same continuous equations run by every successful learning theory ever tried, the smooth dimensionality reduction of singular value decomposition and every deep and fuzzy fad before and since. It’s curve fitting made visual and straightforward. The math is done.” Ed slammed the table. “This is what truth looks like!”

Brutus smiled. He knew those terms, he knew those approaches. Everybody used them. They worked. He nodded with satisfaction. “I’m in.”

Julius and Mark Antony nodded as well. They now understood the problem-space well enough to work toward common goals. According to the theory of Optimum Negotiation this was the best anyone could hope to do: provide enough information to the group so that it can identify and work toward a common goal.

Chairs and pens rustled. After the humans became still, there was only the sound of the air conditioner.

Julius was the first to speak: “I think our work here is done, gentlemen.”

A sudden staccato slap from the end of the table, Pressman’s wooden pen as drumstick,

tap-tap-tap-TAP!

A morse-code fanfare, a second’s silence.

Everyone looked toward him, but Pressman’s face was down in thought.

Again,

tap-tap-tap-TAP!

Then, still without looking up, he mumbled low and ominously,

Beware the March of Idleness….

The others looked from him to Ed, and back.

Ed froze. He knew that phrase from somewhere. But where? He needed time. “Um, I didn’t quite hear you. Could you please repeat it?”

“I said, Beware the March of Idleness . . . . and Ideology.”

Pressman looked up with an open expression, as if stating a simple fact. The others seemed perplexed, but now Ed knew what he was up against: the one thing he was unprepared for.

Pressman continued to speak, his tone shifting from the oracular to the collegial. “That’s a little-known phrase from The Lions.”

Yes! Now Ed recognized it. He’d heard The Lions say that in seminars, but had never seen it written down. Who was this man, and how much did he know?

Pressman went on, “The word ‘March’ refers to the relentless march of changing expectations: the more reliable a source, the more that processors rely on it.” He had the floor, both Ed and the Romans listening enrapt. “‘Idleness’ is the natural, inevitable laziness of informational systems seeking to save resources. The last word, ‘Ideology,’ doesn’t refer to leftist caricatures, but to neutral information-processing strategies so useful that idleness-seeking processors embed them first in conscious processing, but ultimately in unconscious pre-processing as fixed ideas. Such unconscious ideas seem obvious in retrospect, like English spelling.”

Brutus interjected in his aristocratic British, “Or like the English measurement system of feet and inches, which I’m proud to say we English no longer use.” He indulged himself a smirk.

Pressman concluded: “So the ‘March of Idleness’ phrase, in a nutshell, means that not just humanity but any group of information processors will inevitably rely so much on its own informational shortcuts that corruption becomes inevitable, and invisible. It’s why some Lions didn’t want The Ratchet built…it’s only a stopgap itself, doomed to fail like all systems by the mathematical laws of information flow.”

No one knew what to say.

“Not too many people know me personally, nor seem to care. It doesn’t matter. When ideas are clear, it shouldn’t matter who said them. That’s the guiding principle of The Ratchet — it represents the best of our thought, collectively and anonymously. Doesn’t matter who made which part.”

Julius challenged him. “Those caveats may be true, but could have come earlier. Why only now? What are your interests here?”

Pressman looked up and around, his eyes scanning the four walls of the room, not just the faces in it. When he finally steered his open face toward each of the other faces, his steady gaze carried far more vibrational information than any word to any reader.

“I’m from the Second Foundation, not the first, so my title today isn’t important.” he said. “I represent the Wilsof lineage of understanding. We have our own version of the Ratchet, forked from this one at the beginning.” His tone had drifted from collegial back to oracular. “I am privy to the latest simulated predictions from the psycho-history equations. I am here today because together we share a common form of understanding, but each has possibly different facts.” Another hush, mediated by some sub-threshold coherence among quickly inhaled breaths, nail-scrapes, and tilts of chairs. A silence hovered, promising heavy meaning, but not delivering.

Ed knew that name. Wilsof was the earliest and most rebellious of The Lions. He had inspired but then rejected The Ratchet, and now his works were never taught. Ed had thought that name and line of thought were dead.

Pressman stood up and faced the table, as if the table and the four walls were his audience. He declaimed: “An hour ago, given a binary forced choice on that whiteboard, we collectively chose the truth of thermodynamics over the truth of sensory experience. Why is that?”

He paused. The other men in the room remained silently attentive. Pressman continued: “Both truths were topmost. If anyone had asked, we would have realized by the end of our discussion that sensory experience is the only, only, ONLY thing there is in life. Humans can’t sense probability equations, can’t feel them. We must have faith in them, faith in math, which changes slowest of all. But sensory experience is where the bandwidth lies. It carries virtually all the information. Right here, right now, around this amazing table . . . What kind of walnut is it, anyway? What mix of varnish and what grit of sandpaper crafted this magnificent finish? Around this organic masterpiece sit five flesh-and-blood human beings. If what we’re doing is changing the world, we can’t pretend to have some stopping point. Narrative fucks with us that way. It tries to make us drop our guard and rest.”

“This…is…not… a… story,” Pressman enunciated. “Life is continuous. It has no end except death, and even then life continues without the dead. A story needs a beginning, and that needs destabilization, to hold our interest. Later, it needs a closure, a stable end to induce narrative satisfaction, so we can move on to something else. Stories — fake and real alike — are all made from little pieces, but life has no breakpoints and no decision points; those interrupts were invented to keep us focused on work.”

“This is a real meeting, influencing real peoples’ real lives. Life isn’t meant to build cathedrals. Life is meant to live, and at best cathedrals were meant to celebrate life, and not manipulate the attention of the trusting humans sheltering inside them. Humans are sensitive creatures; the more that we trust, the more that attentional manipulation can be a potent pathogen.”

“No narrative closure here,” the untitled man from the Second Foundation said as he stood up. He set down his shimmering wood pen on an unused pad of paper before moving about the room to shake the hands of his compatriots. “The end of a meeting like this isn’t the end of anything real. It’s the beginning of a real job.”